The Civilization of Angkor

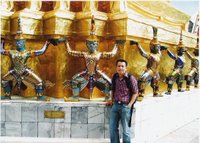

The Civilization of Angkor draws on the latest research on prehistoric archaeology, epigraphy, and art history to reconstruct a detailed chronicle of a remarkable civilization. The book serves as a primer, in addition to the tour guide’s word-of-the-mouth information and perfunctory Lonely Planet coverage, to my recent trip to Angkor Wat and the associated monuments. It illuminates the unique architecture and structural motifs that were dictated by religious influence.

Higham focuses on civilization of Angkor, which was established on the northern shore of the Great Lake (Tonle Sap) in Cambodia, and progressively controlled the Mekong Valley to the delta, the Khorat plateau of northeast Thailand and much of central Thailand. Traces of ruins with Khmer influence are found today in the ancient Siamese capital Ayuthaya, also part of my itinerary.

The Civilization of Angkor traces the origin and developments through four distinct phases, beginning about 500 BC in the prehistoric Iron Age, which saw the origin of rice cultivation. It was significant because domestication of rice represents one of the most profound changes in the human past of Southeast Asia. The second phase (100-550 AD) witnessed a swift transition to organized states in the Mekong delta that was fuelled by participation in a burgeoning international trade network. The third phase (550-800 AD) afforded formation of series of states in the low-lying interior of Cambodia, an area well suited to an agrarian economy. Flood retreat agriculture replenished with silt could provide the necessary rice surpluses to sustain the social elite. Thus the period saw the creation of wealth and establishment of social hierarchy.

My trip to Cambodia focuses on the architectural style quintessential of and the temples erected during the fourth phase (800-1400 AD) of Angkor civilization. Establishment of capital at Angkor was followed by major construction of temples that for four centuries have inspired awe among visitors from all over the world. Higham has highlighted the unique architectural motifs and elaborated on the royal and religious influence that have dictated such motifs.

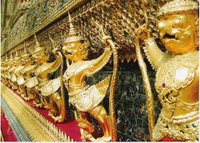

Temples were usually kings’ enduring mausoleums. Kings who ruled for a significant period of time would have a state temple constructed, initially in the form of a raised pyramid to house a

linga (representation of a phallus, usually in stone, that was used as an object of veneration) named after themselves and Shiva (major Hindu god of creation and destruction), which embodied the power of the state. Angkor Wat represented Mount Meru, the home of the Hindu gods, just as the walls and moats symbolized the surrounding mountains and oceans. Kings installed divinized images of their ancestors, whose names were again subtly combined with those of the gods, and worshipped them.

In order to understand the kings’ keen interest to have communion with gods, one has to have a grapple in the historiography of Angkor state and its debt of debt to Indian religion and political philosophy. Beguiled by the ubiquitous imagery of Shiva and Vishnu (the Hindu god of compassion and preservation) and use of Sanskrit (the priestly language of Hinduism), Indianization is often the explanation to origins of Angkor. Hindu myths and tales explain the presence of motifs like the

apsaras (divine nymphs),

nagas (mythical snakes that guard earthly wealth),

asuras (monsters), and rainbow, the bridge between the human world and the gods’ domain.

Kings’ remains were placed in the central tower of Angkor to animate their images. Worship of the dead king ensued once his soul entered his stone image, thus permitting contact with the ancestors of the dynasty. Within this mortuary tradition, Angkor Wat is the preserve of the immortal sovereign with Vishnu, the supreme god who descended to the world of mortals in many guises. Vishnu is often seen with Shiva, whose representation is most remarkable at the nearby Preah Khan, where a

linga, an erect stone phallus is tugged within a

yoni, or vulva.

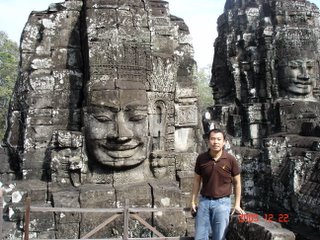

Most of the Angkor temples share a common layout that Higham deftly portrays. A gorupa (entrance pavilion or temple gate) pierces the outer walls. Long rows of galleries sometimes divide up a platform from which a flight of steps leads up to a terrace containing brick towers and laterite structures. Further set of steps flanked by stoned animals lead to the uppermost towers. A maze of shrines and passageways often cluster around the central temple.

A closer look at the central towers at these temples will reveal the difference in architectural style dictated by religious preference: the contention between Hinduism and Buddhism. Cessation of preference for Buddhism led to relentless destruction or modification of every image of the Buddha, including the great statue that once graced the center of Angkor at Bayon Temple. Many smaller shrines at this once-gilded tower were swept away and the site was modified to become a temple to Shiva. Therefore, Bayon contains asymmetric towers: lotus-shaped and

linga. The outer closing wall contains eight cruciform entrance towers, and is covered in bas-reliefs that depict battle scenes and the daily activities of ordinary people. The central shrine, unusually, is circular and must originally have been gilded. A deep shaft under this tower contains the broken parts of a large image of the Buddha, a find reflecting the reaction against Buddhism after the king’s death. On the upper level, one is confronted by the multitude of towers and profusion of enormous heads (smiling faces) gazing serenely into the distance. These are the few remaining intact images.

Drawing from archaeological research, Higham deduces a tower of bronze that used to rise even higher than the gold tower of Bayon Temple. This temple is part of the Baphuon Temple, which is now shrouded in scaffolding. The Royal Palace that lay to the north is now reduced to just two huge

barays (reservoirs) and a few slabs of concrete outlining its foundation. To the east, a once golden bridge flanked by gilded lions led to a pavilion supported by stone elephants. The terrace of elephants is a 300-meter long raised platform. Opposite this parade ground are twelve small towers known as the Prasat Suor Prat. The nearby Ta Prohm is laden with rubbles. Trees have taken hold the temple, enveloped the interior and roots split apart the walls.

The Civilization of Angkor is an academic history of a cluster of cities and their associated monuments that lie between the Great Lake and the Kulen Hills in present Cambodia. Higham traces this unique civilization that began in the prehistoric past and explores Angkor from its earliest foundations. Through the inscriptions and carvings so well preserved that they could have been done yesterday, the book recovers scenes of daily lives and the vicissitudes of the kingdom and deduces causes of its decline and abandonment. The book answers many of the questions pertaining to architectural style and its association to religious preference as I frantically shuttled between temples. Higham’s account allows me to grapple with Angkor’s history, religion, and philosophy in a more strenuous and self-conscious way than the usual come-and-go sightseeing can offer. It gives personal meaning to the whole journey.

The novel is a modern fairy tale under the disguise of a political allegory, the elements of which still bears the shadows if the Cultural Revolution. Mr. Muo’s Travelling Couch represents a conscience – a poignant pang of conscience for social injustice. After years of studying Freud in Paris, a 40-year-old man returns to China to liberate his college sweetheart, who had taken pictures of people being tortured by police and syndicated them to foreign media, under the pretext of interpreting dreams. A corrupted judge mandated virginity of a girl in exchange for clemency from the Communist on her case. So the obsession of a greedy magistrate ensued the psychoanalyst’s journey to find a virgin. The quest took him to a rural panda habitat, brought him to close encounter with the marauding hill tribe, and costed him his own virginity!

The novel is a modern fairy tale under the disguise of a political allegory, the elements of which still bears the shadows if the Cultural Revolution. Mr. Muo’s Travelling Couch represents a conscience – a poignant pang of conscience for social injustice. After years of studying Freud in Paris, a 40-year-old man returns to China to liberate his college sweetheart, who had taken pictures of people being tortured by police and syndicated them to foreign media, under the pretext of interpreting dreams. A corrupted judge mandated virginity of a girl in exchange for clemency from the Communist on her case. So the obsession of a greedy magistrate ensued the psychoanalyst’s journey to find a virgin. The quest took him to a rural panda habitat, brought him to close encounter with the marauding hill tribe, and costed him his own virginity!